- Home

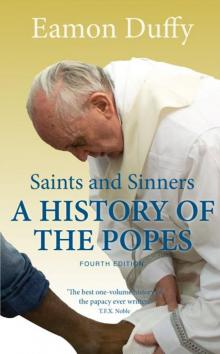

- Eamon Duffy

Saints and Sinners: A History of the Popes; Fourth Edition

Saints and Sinners: A History of the Popes; Fourth Edition Read online

FOR JENNY

Published in association with S4C (Wales)

First published as a Yale Nota Bene Book in 2002

Copyright © Eamon Duffy 1997

New material © Eamon Duffy 2006, 2014

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U. S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publishers.

For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, please contact

U. S. office: [email protected]

Europe office: [email protected]

ISBN-13: 978-0-300-11597-0

Library of Congress Catalog card number for the cloth edition 97-60897

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Printed in Great Britain

10 9 8 7 6 5 4

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Preface to the Second Edition

Preface

1 ‘UPON THIS ROCK’ C. AD 33–461

I From Jerusalem to Rome

II The Bishops of Rome

III The Age of Constantine

IV The Birth of Papal Rome

2 BETWEEN TWO EMPIRES 461–1000

I Under Gothic Kings

II The Age of Gregory the Great

III The Byzantine Captivity of the Papacy

IV Empires of the West

3 SET ABOVE NATIONS 1000–1447

I The Era of Papal Reform

II From Papal Reform to Papal Monarchy

III The Pinnacle of Papal Power

IV Exile and Schism

4 PROTEST AND DIVISION 1477–1774

I The Renaissance Popes

II The Crisis of Christendom

III The Counter-Reformation

IV The Popes in an Age of Absolutism

5 THE POPE AND THE PEOPLE 1774–1903

I The Church and the Revolution

II From Recovery to Reaction

III Pio Nono: The Triumph of Ultramontanism

IV Ultramontanism with a Liberal Face: The Reign of Leo XIII

6 THE ORACLES OF GOD 1903–2005

I The Age of Intransigence

II The Attack on Modernism

III The Age of the Dictators

IV The Age of Vatican II

V Papa Wojtyla

VI The Professor

VII Crisis and Resignation

VIII A Pope for the Poor

Appendix A: Chronological List of Popes and Antipopes

Appendix B: Glossary

Appendix C: How a New Pope Is Made

Notes

Bibliographical Essay

Index

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I owe debts of gratitude to many people: to Harri Pritchard Jones, ‘onlie begetter’, and to his wife Lenna, for their friendship and truly Celtic hospitality. To Opus Television and its staff, in particular to Mervyn Williams, for the invitation to write this book, to Heyden Denman, cameraman, and to Amanda Rees, who directed the television series to which this book is the companion volume. To John Gillanders of Derwen,for endless patience and technical wizzardry. To Yale University Press and especially to Peter James, the copy-editor, to Sheila Lee, who researched the pictures, to Sally Salvesen, who designed the book and nursed it, (and me), through its final stages, and to John Nicoll, prince of publishers. Once again, Ruth Daniel read the proofs out of the goodness of her heart.

PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION

For this new edition of Saints and Sinners, I have taken the opportunity to correct a (thankfully small) number of errors, to expand and revise parts of all but the first two chapters, and to update the Bibliographical Essay. The account of the papacy of John Paul II has been extensively rewritten and augmented, and vigilant readers will detect the modification of some earlier judgements. I have also added a brief appendix explaining the procedures for the election of a new Pope set in place by Pope John Paul II in 1996. The process of revision has greatly benefited from the insights and criticisms of the reviewers of the first edition: I would like to express my particular thanks to Patrick Collinson, T.F.X. Noble and Simon Ditchfield. The illustrations to the first edition elicited much favourable comment, and though it is flattering to the author of a lavishly illustrated book when his publishers reckon his text worth reproducing in its own right, there is inevitably some loss. This edition is less sumptuous than the first, but I hope that the large number of pictures and captions we have retained will continue to extend and deepen the narrative in the text, rather than simply decorate it. I am greatly indebted to Sally Salvesen and to Ruth Applin who designed the new edition. Finally, I renew the heartfelt dedication of this book to my wife Jenny.

Eamon Duffy

Feast of St Mary Magdalene 2001

PREFACE

Nearly 900 million human beings, the largest single collective of people the world has ever known, look to the Pope as their spiritual leader. His office symbolises the rule of God himself over their hearts and minds and consciences. The words of the popes weigh in the halls of power, and in the bedrooms of the faithful. And the papacy is the oldest, as well as arguably the most influential, of all human institutions. The Roman empire was new-born when the first popes ascended the throne of St Peter almost two thousand years ago. When Karol Wojtyla became the 261st Pope in 1978, the dynasty he represented had outlived not merely the Roman and Byzantine empires, but those of Carolingian Gaul, of medieval Germany, of Spain, of Britain, and the Third Reich of Hider. Wojtyla himself was to play a not inconsiderable role in the collapse of the latest of these empires, the Soviet Union.

In the flux of history, the papacy has been, not a mere spectator, but a major player. As the Roman empire collapsed, and the barbarian nations arose to fill the vacuum, the popes, in default of any other agency, set themselves to shape the destiny of the West, acting as midwives to the emergence of Europe, creating emperors, deposing monarchs for rebellion against the Church. Popes have divided the known and yet to be discovered world between colonial powers for the sake of peace, or have plunged nations and continents into war, hurling the Christian West against the Muslim East in the Crusades.

The history of the papacy is therefore the history of one of the most momentous and extraordinary institutions in the history of the world. It has touched human society and culture at every point. From contemporary concern with issues of life and death, the morality of abortion or the death-penalty, of capitalism or of nuclear war, to the history of Western art and the major commissions of Michelangelo and Raphael, Bramante and Bernini, the papacy has been and remains still at the heart of many of the most urgent, the most profound and the most exuberant of human concerns.

This book, which is linked to a series of six television programmes, attempts to provide an overview of the whole history of the papacy from the Aposde Peter to Pope John Paul II. It traces the process by which Peter, the humble fisherman of Galilee, became the figurehead and foundation stone of a dynasty which has been able to challenge the most powerful secular rulers, and which commands the religious allegiance of more than a fifth of the worlds population. The book is not a work of theology, though no history of the papacy can or should altogether avoid theology. I have tried to include enough theological explanation to enable the non-specialist reader to understand the milestones in the emergence of the papacy as a religious and political institution, but I have not thought it my business to justify or defend that evolution. For Roman Catholics, of course (of whom I

am one), the story of the popes is a crucial dimension of the story of the providential care of God for humankind in history, the necessary and (on the whole) proper development of powers and responsibilities implicit in the nature of the Church itself. But by no means all Christians accept such a claim, and for some the papacy, at least in its modern form, is a disastrous cul-de-sac, and a prime cause of Christian disunity. For non-Christians the story of the popes is simply one more of the myriad stories of humanity, another of the multiple forms in which human hope and human ambition have expressed themselves. Whatever the reader’s convictions, however, I hope that the narrative offered here provides a framework for understanding one of the world’s longest-enduring and most influential institutions.

This is a history of the popes: it cannot claim to be the history of the popes. No one-volume survey of an institution so ancient and so embedded in human history and culture can be anything more than a sketch, just as no historian can claim equal competence and grip across a 2,000-year sketch. There is no single storyline, for history does not evolve in lines, and the papacy has been at the centre of too many different human stories and enterprises for it to have a single story of its own. Themes do of course recur. In writing the book I have been struck by the extent to which the mere existence of the papacy, and even its most self-aggrandising claims, have again and again helped ensure that the local churches of Christendom retained something of a universal Christian vision, that they did not entirely collapse back into the narrowness of religious nationalism, or become entirely subordinated to the will of powerful secular rulers. From Barbarian Italy or Carolingian Europe, to the Age of Enlightenment, or the Age of the Dictators, the papacy has helped keep alive a vision of human value which transcended the atavisms of history and the rule of mere force, and has borne witness to the objectivity of truths beyond the shifts of intellectual fashion. For all its sins, and despite its recurring commitment to the repression of ‘error’, the papacy does seem to me to have been on balance a force for human freedom, and largeness of spirit.

I have tried to ensure that the narrative offered here is reasonably comprehensive, and that it accurately reflects the current state of knowledge of the issues and events it covers. Inevitably, however, the attempt to compress so much into so small a space has involved drastic and painful decisions about what to omit, as well as what to include: I do not expect my judgement about what is central and what marginal to be agreed with by everyone.

Nor is every stretch of papal history equally easy going. Some readers may be daunted by the theological complexities and the historical unfamiliarity of some of the material covered in Chapter Two, which deals with the popes of the so-called ‘Dark Ages’. I have dealt with them in some detail, however, because the fundamental orientation of the papacy towards the West and away from the East was decided in those centuries. Similarly, in the section on the Renaissance popes, readers may be surprised to find far more about the relatively obscure Nicholas V than about the far more notorious Alexander VI, the ‘Borgia Pope’. This is not because Nicholas was respectable and pious, and Alexander scandalous and debauched (though both these things are true), but because in my view the career of Nicholas V tells us far more about the nature and objectives of the Renaissance papacy than the more colourful and better-known escapades of Alexander. Readers must judge for themselves. And finally, it is of course too soon to form a mature assessment of the nature or importance of the pontificate of John Paul II, or indeed those of his immediate predecessors. More than any other part of the book, the final chapter is offered as a tentative interim report, and a personal perspective.

I have tried not to clog the text with too many technical aids. A light sprinkling of reference notes identifies extended or contentious quotations, while more detailed guidance to the literature on any given subject will be found in the chapter-by-chapter and topic-by-topic Bibliographical Essay at the end of the book. A Glossary provides brief explanations of technicalities; I have included also a numbered chronological list of popes and anti-popes.

Eamon Duffy

College of St Mary Magdalene, Cambridge

Feast of Sts Peter and Paul, 1997

CHAPTER ONE

‘UPON THIS ROCK’

c. AD 33–461

I FROM JERUSALEM TO ROME

Round the dome of St Peter’s basilica in Rome, in letters six feet high, are Christ’s words to Peter from chapter sixteen of Matthew’s Gospel: Tu es Petrus, et super hanc petram aedificabo ecclesiam meam et tibi dabo claves regni caelorum (Thou art Peter, and upon this Rock I will build my Church and I will give to thee the keys of the Kingdom of Heaven). Set there to crown the grave of the Apostle, hidden far below the high altar, they are also designed to proclaim the authority of the man whom almost a billion Christians look to as the living heir of Peter. With these words, it is believed, Christ made Peter prince of the Apostles and head of the Church on earth: generation by generation, that role has been handed on to Peters successors, the popes. As the Pope celebrates Mass at the high altar of St Peters, the New Testament and the modern world, heaven and earth, touch hands.

The continuity between Pope and Apostle rests on traditions which stretch back almost to the very beginning of the written records of Christianity. It was already well established by the year AD 180, when the early Christian writer Irenaeus of Lyons invoked it in defence of orthodox Christianity. The Church of Rome was for him the ‘great and illustrious Church’ to which, ‘on account of its commanding position, every church, that is the faithful everywhere, must resort’. Irenaeus thought that the Church had been ‘founded and organised at Rome by the two glorious Apostles, Peter and Paul,’ and that its faith had been reliably passed down to posterity by an unbroken succession of bishops, the first of them chosen and consecrated by the Apostles themselves. He named the bishops who had succeeded the Apostles, in the process providing us with the earliest surviving list of the popes – Linus, Anacletus, Clement, Evaristus, Alexander, Sixtus, and so on down to Irenaeus’ contemporary and friend Eleutherius, Bishop of Rome from AD 174 to 189.1

All the essential claims of the modern papacy, it might seem, are contained in this Gospel saying about the Rock, and in Irenaeus’ account of the apostolic pedigree of the early bishops of Rome. Yet matters are not so simple. The popes trace their commission from Christ through Peter, yet for Irenaeus the authority of the Church at Rome came from its foundation by two Apostles, not by one, Peter and Paul, not Peter alone. The tradition that Peter and Paul had been put to death at the hands of Nero in Rome about the year AD 64 was universally accepted in the second century, and by the end of that century pilgrims to Rome were being shown the ‘trophies’ of the Apostles, their tombs or cenotaphs, Peter’s on the Vatican Hill, and Paul’s on the Via Ostiensis, outside the walls on the road to the coast. Yet on all of this the New Testament is silent. Later legend would fill out the details of Peter’s life and death in Rome – his struggles with the magician and father of heresy, Simon Magus, his miracles, his attempted escape from persecution in Rome, a flight from which he was turned back by a reproachful vision of Christ (the ‘Quo Vadis’ legend), and finally his crucifixion upside down in the Vatican Circus in the time of the Emperor Nero. These stories were to be accepted as sober history by some of the greatest minds of the early Church – Origen, Ambrose, Augustine. But they are pious romance, not history, and the fact is that we have no reliable accounts either of Peter’s later life or of the manner or place of his death. Neither Peter nor Paul founded the Church at Rome, for there were Christians in the city before either of the Apostles set foot there. Nor can we assume, as Irenaeus did, that the Apostles established there a succession of bishops to carry on their work in the city, for all the indications are that there was no single bishop at Rome for almost a century after the deaths of the Apostles. In fact, wherever we turn, the solid outlines of the Petrine succession at Rome seem to blur and dissolve.

That the leadership of the Christian Church

should be associated with Rome at all, and with the person of Peter, in itself needs some explanation. Christianity is an oriental religion, born in the religious and political turmoil of first-century Palestine. Its central figure was a travelling rabbi, whose disciples proclaimed him as the fulfilment of Jewish hopes, the Messiah. Executed by the Romans as a pretender to the throne of Israel, his death and resurrection were interpreted by reference to the stories and prophecies of the Jewish scriptures, and much of the language in which it was proclaimed derived from and spoke to Jewish hopes and longings. Jerusalem was the first centre of Christian preaching, and the Church at Jerusalem was led by members of the Messiah’s own family, starting with James, the ‘brother’ of Jesus.

Within ten years of the Messiah’s death, however, Christianity escaped from Palestine, along the seaways and roads of the Pax Romana, northwards to Antioch, on to Ephesus, Corinth and Thessalonica, and westwards to Cyprus, Crete and Rome. The man chiefly responsible was Paul of Tarsus, a sophisticated Greek-speaking rabbi who, unlike Jesus’ twelve Apostles, was himself a Roman citizen. Against opposition from fellow Christians, including Jesus’ first disciples, Paul insisted that the life and death of Jesus not only fulfilled the Jewish Law and the Prophets, but made sense of the world, and offered reconciliation and peace with God for the whole human race. In Jesus, Paul believed that God was offering humanity as a whole the life, guidance and transforming power which had once been the possession of Israel. His reshaping of the Christian message provided the vehicle by which an obscure heresy from one of the less appetising corners of the Roman Empire could enter the bloodstream of late antiquity. In due course, the whole world was changed.

Saints and Sinners: A History of the Popes; Fourth Edition

Saints and Sinners: A History of the Popes; Fourth Edition